Eddie James “Son” House, Jr. (1902 – 1988) was, at different times of his life, a Baptist deacon and a Delta blues singer. This meeting of the sacred and the profane, the secular and the spiritual, made Son House a fevered and intense guitar player with a voice both powerful and unrestrained.

When he was in his early teens, Son House’s family left Mississippi and moved to Algiers in New Orleans. Recalling these years, he would speak of his hatred of blues music and his passion for the Church. At fifteen he began preaching sermons and was accepted as a paid pastor, first in the Baptist Church and then in the Colored Methodist and Episcopal Church. However, he fell into habits which conflicted with his calling – drinking (like his father) and womanizing. This led him, after so many years of hostility towards secular music, to leave the church and turn to the blues at the age of 25. He quickly developed a unique style by applying the rhythmic drive, vocal power and emotional intensity of preaching to his blues vocabulary.

In 1928, Son House was playing in a juke joint when a man went on a shooting spree, wounding House in the leg. House shot the man dead in self defense but was convicted of manslaughter and received a 15-year sentence at the Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm), of which he served two years. Upon his release, bluesman Charley Patton invited him to share engagements and to accompany him to a 1930 recording session for Paramount Records. Issued at the start of the Great Depression, the records did not sell and House remained unknown at the national level. However, he was very popular locally and, together with Patton’s associate, Willie Brown, he became a leading regional performer and a formative influence on Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters. In 1941 and 1942, he was recorded by the great American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. The following year, he left the Mississippi Delta for Rochester, New York and gave up music.

In 1964, House was “rediscovered” in Rochester and was completely unaware of the 1960s folk and blues revival and the international enthusiasm for his early recordings. He subsequently toured extensively in the United States and Europe and started recording again. Like Mississippi John Hurt, he was welcomed with open arms into the music scene of the 1960s and played at the prestigious Newport Folk Festival in 1964, the New York Folk Festival in 1965 and the 1967 European Tour of the American Folk Festival, along with some of the very best bluesmen like Skip James and Bukka White.

Ill health plagued House in his later years, and in 1974 he retired once again. He later moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he remained until his death from cancer of the larynx in 1988. He was buried at the Mt. Hazel Cemetery and members of the Detroit Blues Society raised enough money through benefit concerts to put a monument on his grave.

When I first saw Son House play “Death Letter” on one of those folk revival TV shows of the late 60s, it marked me for life. There, the secular and the spiritual collided and sparked off one of the most impelling performances in the history of the blues. House plays his resonator guitar with a piece of copper tubing for a slide, his right hand circling and pounding the strings. His voice is that of a preacher in his pulpit. His performance is, for me, proof of the existence of God and, probably, of the Devil as well. Here is the link to see this video :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NdgrQoZHnNY

Quite apart from this magnificent performance are the lyrics. At a time when pop music was all flowers and sunshine, Son House spoke of death, of a corpse on a cooling board during the preparation for burial, of the viewing of the corpse, of the graveyard taken over by crowds of people and of the slow descent of the coffin in the grave. It was my fate to know these things at an early age and my performance of “Death Letter” here is certainly psychotherapeutic.“Death letters” are a service offered by the postal administrations of most countries to help the grieving family communicate the death of a loved one to the public. Typically, the letters are pre-printed with the appropriate sentiments and bordered in black, as are the envelopes used.

I am extremely fortunate to count on the musical support of Alrick Huebener and Roch Tassé, two of the finest musicians in the Ottawa Valley.

Richard Séguin – voice, electric guitars

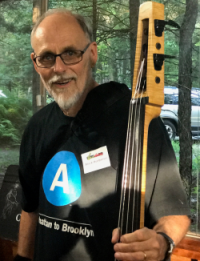

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Roch Tassé – drums

Ajouter un mot

You must be logged in to post a comment.