In 1965, Dylan opened his monumental and controversial set at the Newport Folk Festival with “Maggie’s Farm”, a song from his recent album, “Bringing It All Back Home.” It was the first time he went on stage with an electric band, much to the consternation of the crowd. To learn more about this era and the profound changes Dylan struggled with, click here.

I was the biggest fan of Dylan’s new electric music and “Maggie’s Farm” was, and still is, at the very top of my favourites. However, in 1965, I had no idea that “Maggie’s Farm” would occupy such a special place in my life.

By the end of my adolescence, I had decided that I wanted to be an educated man. I had two friends, André “Red” Henri and Jean-Pierre Béland, who were educated and both of them spoke like a bird sings – extended vocabularies, sure expressions, I could have listened to them speak all day. So, when I finished high school, I took aim at university, looking to get educated. This was not without problems. The university was in Ottawa and I was in Rockland. I had no car, no money and my parents couldn’t afford to pay for my studies. In my mind, my entire life depended on achieving a successful education so I borrowed money from the bank and I rode the bus to Ottawa every morning, coming back home every night.

One of my new classes ended at 11 PM and there was no bus service at that hour. I tried changing the hours of my course but this was 1968-69 and the students had suddenly become ultra-cool hippies – they had occupied the administration building and were protesting against the war, the laws, everything except pot. The university administration communicated with the students by stapling flyers on the telephone poles telling us where we could reach them on a daily basis. The problem was that I never read public notices. I lost sight of the already dreary path of my courses.

In those classes, the professors were disinterested and the curriculum was no more than a race for them – they all wanted to finish as soon as possible. If I asked a question, they politely answered that the question was interesting but that we didn’t have the time to get into that. My illusions totally shattered, I talked to Jean-Pierre in the cafeteria – Jean-Pierre was finishing his last year while I was starting my first. Not for the last time, my friend gave me his support and made me understand that I could educate myself (we read books back then) and perhaps in a better way than in the organized methods of the province. I left university in February 1969, a total failure in my own eyes.

I would be remiss not to mention that both Alrick and Roch, my musical sidekicks, sucessfully completed their university studies. Alrick went to Eastern Washington State College, working summers in construction back home in Cranbrook B.C. to pay for his tuition. Like me, he was lonely, didn’t feel ready and quit after his first semester. Ill suited to the forestry, construction and mining jobs available to uneducatied youths, Alrick went back to school and found his way to the social sciences and a degree in psychology. After three years in Vancouver, Alrick studied journalism at Carleton University and earned his masters degree in 1984, the only one in his immediate family to do so. Roch, who is also from Rockland and who has been a good friend since high school, was in the same predicament as I was. His mother raised him and his sister on her own and the family had no money for tuition. Like me, Roch had to borrow money from the bank and ride a bus to Ottawa and back. Unlike me, Roch persevered for three long years and earned his baccalaureate in Political Science.

I started working in September but teenagers without diplomas don’t get the best jobs. I worked on sorting and delivering mail in a basement room of the Sir John Carling Building, which doesn’t exist anymore but was occupied by the Ministry of Agriculture at that time and was part of Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm. To get to work, I drove in with Mr. Fernand Laporte and Mr. Ovila Diotte, both from Rockland and both elegant in their suits and ties, me, not so much. Mr. Laporte, also a very educated man, was the best whistler I ever met in my life. Roger Whittaker would have been put to shame. Mr. Laporte was captivated by the classical music we listened to on the radio and he whistled to his heart’s content. It was like travelling with a bird and, with a lot of practice, I also learned to whistle pretty well, thanks to Mr. Laporte.

The work was boring but I had three friends in the mail room. Jim, a very intelligent anglophone a little older than I was, had anticipated the “goth” style by several years. This was a new world to me – we didn’t have goths in Rockland. Jim was tall, wore a long black coat that went to his ankles, black jeans and black t-shirt, black Army boots and even his long hair was dyed black. His favourite group was the Rolling Stones and he lived for the profound negativity of their lyrics, like “Heat of Stone”, “Under My Thumb” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Jim even looked like Jagger!

My second friend, Marcel, was a guy from the streets of Hull, maybe six years older than I was. Nature had not been kind to Marcel – he was skinny and had a hook nose, his hair was short and unruly and he only had a few teeth left, all of them rotten! Marcel was a romantic and spoke to me endlessly of his girlfriend. He quickly saw that I was a naïve country guy and he became in some ways my protector, almost an older brother. Particularly, Marcel hid me from one of the civil servants on the third floor, a very vulgar and predatory homosexual with an affinity for young francophones. Marcel convinced him that I neither spoke nor understood French, which did not prevent him from verbally tormenting me all the more, thinking that I didn’t understand what he said. Seeing this, Marcel took over the delivery of this monster’s mail in my place. A friend like few others, Marcel.

My third friend was called Doug but everybody knew him as Dougie, a tall thirtyish man that people thought was retarded but I just saw him as a simple man, uncomfortable with the complicated interactions that people juggled amongst themselves. He lived with his mother, whom he loved very much. He also had something that none of the other workers had – enthusiasm. Dougie could sort and deliver mail like nobody else. He was good at his job, proud of himself and he was happy, spreading his joy to every floor of the building. Everyone loved Dougie. That is to say, everyone loved Dougie except one person – the mail room manager.

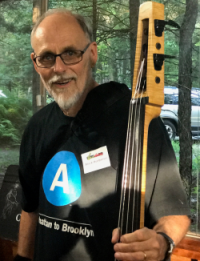

Alrick Huebener

He was an ex-Army type, thick in the torso and thick in the head, always angry, undoubtedly frustrated by his miserable life. He blamed Dougie for everything because Dougie never talked back. Dougie just looked at the floor in shame, never understanding what it was he had done wrong. I started hating my boss more than I hated Hitler and I wanted to hurt him like he hurt Dougie. So I waited for the busiest time of the year, two weeks before Christmas, and I went into his office and told him something unforeseen had happened and I needed to quit immediately, leaving him shorthanded. He was furious, very disappointed in me but I left the mail room with a smile on my face.

Back in Rockland, I felt like a total failure but I was nineteen years old. Nineteen-year-olds don’t stay moody too long. They have support mechanisms, lots of them. In my mind, I started equating the Experimental Farm with “Maggie’s Farm” – that place where East is somewhere West and everything low is on one of those floors higher up. I kept the door to my room shut, banging on my guitar and singing that delicious Dylan diatribe at the top of my lungs – “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more!” It was music as emotional liberation. Hearing those cries and howls emanating from my room, my poor mother, not for the first nor for the last time, surely thought that her son had finally gone mad.

Richard Séguin – electric guitars, voice

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Roch Tassé – drums

Maggie’s Farm