The McGarrigle sisters, Kate (1946-2010) and Anna (b. 1944) are Canadian singer-songwriters and multi-instrumentalists from Montreal, Quebec. Although associated with Montreal’s anglophone community, they grew up in the Laurentian Mountains village of Saint-Sauveur-des Monts and are perfectly bilingual. Born of French-Canadian and Irish parents, the sisters studied piano at the local convent. Elder sister Jane completed the family singing sessions around the living room piano, a regular occurrence.

Kate studied engineering at McGill University, and Anna painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal. Kate learned the banjo after watching Pete Seeger and joined Anna and two friends in 1962 to form the Mountain City Four, a group specializing in roots music, particularly the songs of the Carter Family. After earning an engineering degree from McGill, Kate moved to New York to continue her musical career while Anna stayed in Montreal. Kate performed in the clubs of Greenwich Village and in 1971 married singer Loudon Wainwright III, who wrote “Swimming Song.” They have two children, Martha and Rufus Wainwright, both well established musicians.

Over the years the McGarrigles’ songs have been recorded by Judy Collins, Marianne Faithful, Emmylou Harris and Nana Mouskouri, among others. The sisters also performed and recorded with the world-renowned Irish group The Chieftains, folk music icon Joan Baez and Quebec’s legendary songwriter Gilles Vigneault.

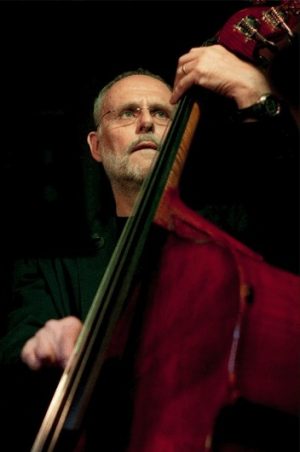

In 1975, the sisters released their first album, simply titled “Kate and Anna McGarrigle.” Thanks to their songwriting skills, the close ties they had cultivated throughout the North-American music industry was repaid with the participation on this recording of some of the world’s best musicians, including bassist Tony Levin (King Crimson, Peter Gabriel), guitarist Lowell George (Little Feat) and studio professionals like drummers Steve Gadd and Russ Kunkel, saxophonist Bobby Knight, guitarists David Spinozza, Hugh McCraken, Tony Rice, Amos Garrett and Andrew Gold, and the extraordinary mandolin of David Grisman. The album won Melody Maker’s Album of the Year Award.

The McGarrigles recorded 13 albums during their career. In 1980, they permanently endeared themselves with the entire Quebec population by releasing the album “Entre la jeunesse et la sagesse” (Between Youth and Wisdom), which was sung entirely in French. In 2003, they released a second entirely French album titled “La vache qui pleure” (The Crying Cow). They have appeared in concerts and festivals in all parts of Canada and the United States, in England, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, and Hong Kong. They were appointed Members of the Order of Canada in 1993 and received the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award in 2004.

In 2006, Kate became progressively ill with clear cell sarcoma, a rare form of cancer. She died in 2010 and, in gratitude for the care she had received, she endowed a fund at McGill University to support cancer research and care in Montreal. Emmylou Harris, a very close friend, wrote and recorded the ballad “Darlin’ Kate” in her memory.

Kate’s tombstone is, not surprisingly, a work of art. The front is embellished with one of Kate’s most famous drawings, never titled, but known affectionately as “ski girl.” The back is engraved with the image of a banjo and the words to one of the sisters most moving songs, “Talk To Me Of Mendocino.”

Let the sun set on the ocean

I will watch it from the shore

Let the sun rise over the redwoods

I’ll rise with it till I rise no more

Situated on the shores of the Pacific Ocean in California, the community of Mendocino is known for its natural beauty and its artist colony.

Situated on the shores of the Pacific Ocean in California, the community of Mendocino is known for its natural beauty and its artist colony.

Anna McGarrigle is married to Canadian journalist and author Dane Lanken. The couple have two children, Lily and Sylvan, and live in North Glengarry, Ontario, just west of the Quebec border.

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, banjo, mandolin, electric bass guitar