50th wedding anniversary of my grand-parents, Joseph Séguin and Rose Délima Blanchette, 1955. From L to R., Jean-Guy Séguin, Marielle Séguin, Gabriel Séguin, my cousin Gisèle Labrèche and my cousin Réjean Labrèche

As far back as I can remember, my hometown of Rockland has been filled with amateur musicians, in the sense that no one paid them to make music. They played because they loved to play. However, they were talented. I’ve always thought that music played simply out of love is as pure as this art form can be.

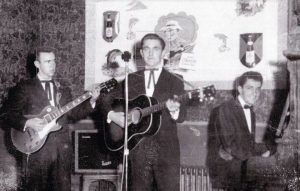

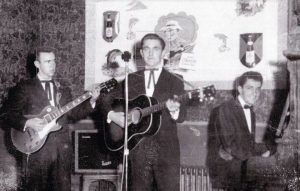

The Happy Valley Boys at the Windsor Hotel. From L to R, Gerry Sharp, Paul Labelle, Gabriel Séguin

When I was a boy, there was always music in our home. My brother Gabriel formed a band called The Happy Valley Boys, with his friends Paul Labelle and Gerry Sharp. They often played at the Windsor Hotel on the corner of Metcalfe and Queen in Ottawa, and even played as far as Maniwaki. My extended family followed them everywhere. Paul and Gerry were always with us when Gabriel was alive, brothers those three. They ate under our roof, slept under our roof and my parents loved them as their own.

One of our famous local musicians is Gaëtan “Pete” Danis, an excellent guitarist who played for decades behind Bob and Marie King, a very popular duo, especially in Quebec and eastern Ontario. The group was completed by Hughie Desmond on electric bass and Gilles St-Laurent on drums. Gilles also played with The Happy Valley Boys on occasion.

Michel Rondeau of Rockland is a trumpeter and graduate of the Conservatoire de Musique du Québec, who composed more than 200 works including 35 symphonies, and transcribed and arranged more than 900 choral and organ works, as well as pieces for various combinations of instruments and voices. When I was a young man, I often went to Michel’s home with my guitar to accompany him while he played popular trumpet pieces of the time. He was particularly fond of Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass and Henry Mancini.

The Rockland Marching Band

Michel Rondeau, like many boys and men from Rockland, also went through the Rockland Marching Band. My brother Bob and I were there for a few years. A friend of Bob’s and a member of the Marching Band, Jacques Drury, came over to practice his saxophone while my brother played his guitar.

The Lalonde family of Rockland formed an orchestra composed of Pat Pilon, singer and guitarist, Aurèle Lalonde, proclaimed the best fiddler in Eastern Canada, his brother «Tit-Bus» on bass, Gaston Leroux on drums and an excellent steel guitar player from Bourget whose name is lost in history.

In Rockland, there was always someone to help a young person learn music. Roch Tassé, an excellent drummer and friend of mine who has often collaborated with me to produce the pieces presented on this site, was often visited by his uncle Ubald Pilon, a fiddler, accompanied by his musician friends. Pat Pilon was there as well as Gaston Leroux, who taught Roch the drums. His uncle Ubald taught him the basics of the guitar. The Rockland Pilon family also formed an orchestra led by Fernand Pilon, who had a heating oil delivery business in town. His younger brother Denis Pilon played drums.

A band called «The Royals» had been formed to be the orchestra in residence of the King George Hotel in Rockland, but they also played in Thurso, Que. The members were André “Gus” Gosselin, an excellent drummer and singer, Denis Tessier, a superb guitarist who influenced me a lot in my early days, Jean-Pierre Ménard, guitar and Michel Chrétien, another former student of the Rockland Marching Band on the saxophone.

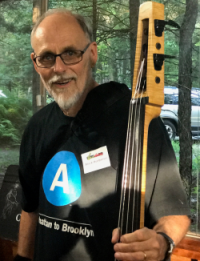

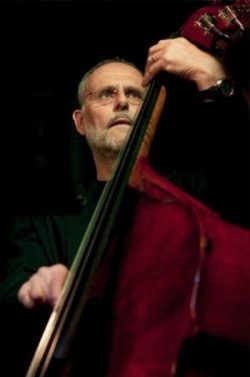

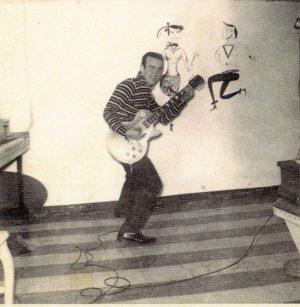

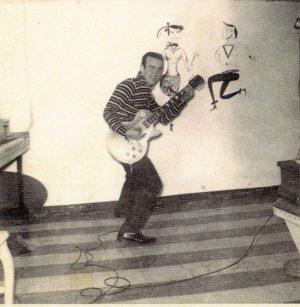

Gerry Sharp in our basement, circa 1957.

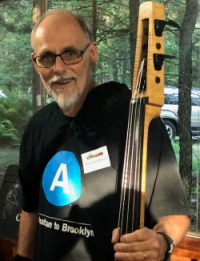

The Sharp family was also very active in music. Gerry, who played with my brother Gabriel, became a classical guitar teacher and worked for a long time at Gervais Electronics in Ottawa. His brother Arthur played guitar and sang, often accompanied by my great friend Gilles “Blaze” Dessaint (1946-2019). When they played in person, Richard Rochon was their drummer.

The SynComs. From L to R, Côme Boucher, Richard Houle, Robert Aquin, Bob Séguin and Tom Butterworth

In 1963, my brother Bob formed a high school band with Côme Boucher, Richard Houle, Robert “Bob” Aquin and Tom Butterworth. It was the birth of the communications era and the American Syncom progtram, founded by NASA in 1963, launched Syncom 2, the first geosynchronous communications sattelite, meaning that its orbit matched that of the earth, one revolution each day. Suddenly, the world got a whole lot smaller. Not surprisingly, the band took on the name of The Syncoms.

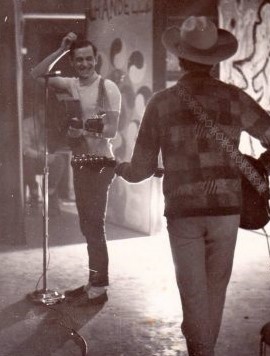

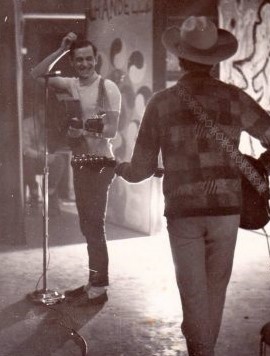

Tom and Richard at La chandelle. Sitting in the wings, Roch Tassé

I joined my brother’s band in 1965. Bob loved the British band Gerry and The Pacemakers and called his band Robbie and The Trendsetters, then The Trendsetters and finally, just The Trend. The band was completed by Tom Butterworth on guitar and Denis Sabourin, a drummer from Hammond. Tom and I then played with André «Gus» Gosselin and we also played as a duo at La chandelle, a meeting place for young people in the basement of the Rockland Church. Roch Tassé directed many of the activities at La chandelle.

In 1966, a song called «Elusive Butterfly» was a big hit for singer Bob Lind and a Rockland band was formed with the name The Elusive Butterflies, formerly called The Rubies. The musicians included Don Boudria, voice and guitar, Denis Bergeron, guitar, André Parisien and Pierre Castonguay, electric bass and Pierre Lemay on drums. In 1984, Don Boudria was elected as the Liberal representative for the riding of Glengarry-Prescott-Russell in Ontario. He held various positions in Jean Chrétien’s cabinet when he took office in 1993, including House Leader and Minister of Public Works.

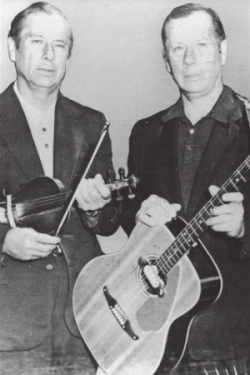

Richard and Alcide Dupuis

I had the chance to play many times with Alcide Dupuis, a Rockland fiddler. An uncle of Alcide’s had taught him the fiddle but little else! Alcide knew neither note nor key and kept a varied and very sophisticated repertoire of tunes in his head. The problem was retrieving a tune from his memory! He began by scratching out a few notes on the the strings with his bow, looking for an uncertain melody. Alcide was also a tremendous stepper and his feet would try to find the rhythm that went with the melody. He gradually got closer to his goal, found it, and took off like a 747, all elbows, bow and feet! It was one of the most spectacular transformations I’ve ever witnessed in my life. As you can see from the photo, we had a whole lot of fun.

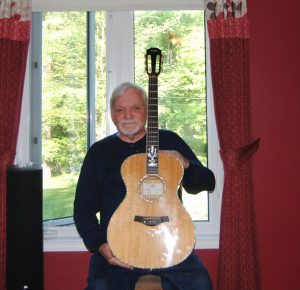

I was working at the time and was able to buy an acoustic guitar, an electric guitar (both Gibsons) and a Fender banjo. Tom Butterworth bought his first steel guitar and these instruments allowed us to diversify into the different genres we liked. Finally, Richard Houle (electric bass) and Pierre Lemay (drums) joined Tom and I to form a band that never had a name. In 1971, my brother Bob bought a Sony tape recorder, the height of recording technology at the time. My brother recorded us playing first in the basement of our home and, in 1972, in the basement of Pierre Lemay’s home. Nothing became of the tapes and they were stored in various places and forgotten for over 30 years.

In the basement of La Ste Famille, Rockland’s cultural center. From L to R, Manu, Richard Séguin, Alain Gratton, Jean-Pierre Béland

Tom later formed a band called Beach, which also included Pierre Chénier (1953-2021) on guitar, Richard Houle on electric bass and his cousin John Houle on drums. Meanwhile, I started writing songs for guitar and banjo. My friend Jean-Pierre Béland, an expert in audiovisual productions, asked me to compose the soundtrack for a slideshow he was putting together. Jean-Pierre recorded me in the vestry of the Rockland Church where the natural reverberations are striking. The results were very well received and, in 1975, Jean-Pierre drove Roch and I to a small studio in Montreal called Bobinason to make our first commercial recordings.

Around 2008, Richard Houle phoned me to tell me that he had found the 1972 tapes in a box in his basement. Richard came to visit me and gave me the tapes, which I then gave to my brother Bob. Bob still had this old Sony tape recorder and it was still working! Thanks to his digital equipment of the time, he was able to transfer our original recordings from the tapes to digital audio media. The tapes, then over 40 years old, had deteriorated and the original recordings were affected, but some were better than others. One of the best is our interpretation of “Long Black Veil”. How Bob managed to record four instruments and four voices with only two microphones I’ll never know.

“Long Black Veil” was composed by Danny Dill (1924-2008) and Marijohn Wilkin (1920-2006), two professional songwriters, and was first recorded by William Orville “Lefty” Frizzell (1928-1975) in 1959. Frizell is known as one of the most influential country stylists of all time. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1982.

“Long Black Veil” has become a standard and has been covered by a variety of artists in the country, folk and rock styles, including Johnny Cash and The Band.

This recording, lost and found, is dedicated to the memory of Richard Houle (1947-2013).

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar

Tom Butterworth – voice, electric guitar

Richard Houle – voice, electric bass

Pierre Lemay – drums

Bob Séguin – voice, analog recording, digital transfer

To hear the song, click on the title below.

Long Black Veil 1972