Hard is the fortune of all womankind

They’re always controlled, they’re always confined

Controlled by their parents until they are wives

Then slaves to their husbands the rest of their lives

“The Wagoner’s Lad,” traditional song collected and published in 1916.

Originally labeled as “mountain music” or “hillbilly music,” the rural music of the 1920s was a very far cry from the multi-billion-dollar international industry that we now call “country music.” In its original sense, country music, i.e. music made by people from rural areas, was what the cajuns call “la vraie chose, chère.” It was the music of life, warts and all, some of it coming across oceans of time from the British Isles, some of it coming from the local cotton mill, mine or tavern.

Commercial recordings of country music began in 1922 with such artists as Uncle Dave Macon and Vernon Dalhart traveling to New York City to record in the studios of the major record labels. For more information about Uncle Dave Macon and his music, click here.

With the advent of electrical recordings in 1925, equipment became much more sophisticated and much more portable. In 1927, producer Ralph Peer (1892-1960) of the Victor Talking Machine Company took a two-month trip through the southern Appalachian cities of Savannah, Georgia, Charlotte, North Carolina and Bristol, Tennessee to record different styles of country music played by artists who would have been unable to travel to New York. At the time, personal contact among musicians was the main connection that had allowed old songs to be kept alive, The music was played and sung from grandparents to parents and from parents to children.

Peer recognized the potential of mountain music, as even residents of Appalachia who didn’t have electricity often owned hand-cranked Victrolas or other phonographs. Coupled with the advent of more powerful radio stations which brought country music into homes all across Appalachia, the orthophonic recording technology made it possible for people to listen to music whenever they liked.

Peer set up his recording facility and, through radio and newspaper ads, invited musicians to come to Bristol and get paid to record their music. The recordings that followed, often described as the “big bang” of country music, led to the discovery of two of the greatest talents of this era, Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. For more information about Jimmie Rodgers and his music, click here.

The Carter Family came from Virginia and was comprised of A.P. (Alvin Pleasant) Carter (1891-1960), his wife Sara Carter (1898-1979) and Sara’s cousin and sister-in-law Maybelle Carter (1909-1978) who was married to A.P.’s brother Ezra “Eck” Carter (1898-1975). Throughout the group’s career, Sara Carter sang lead vocals and played rhythm guitar or autoharp, while Maybelle sang harmony and played lead guitar. On some songs A.P. did not perform at all; on others he sang harmony and background vocals and occasionally sang lead.

Maybelle’s distinctive guitar style became a hallmark of the group, and her “Carter Scratch,” as it came to be known, has become one of the most widely copied styles of guitar playing. It was a way of playing both lead and rhythm, making the guitar a lead instrument and inspiring countless musicians after her. Case in point, when I was 13 and learning to play the guitar, the first song I learned to play was the Carter Family’s “Wildwood Flower” which featured Maybelle’s artistry. Every kid learning the guitar at that time learned “Wildwood Flower,” one of the most didactic pieces ever written. An African-American guitar player called Lesley Riddle taught Maybell how to simultaneously play melody and rhythm. Riddle accompanied A.P. Carter on several of his “song-catching” trips he made in order to collect songs to play and record after the Bristol Sessions.

“Single Girl, Married Girl” was the Carter Family’s second 78-rpm record for the Victor Records label, recorded on August 2, 1927. This version was later included in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, the blueprint for the 1960s folk revival. Notably, the song does not feature A.P. Carter, but is instead a solo by Sara Carter playing autoharp accompanied by her cousin Maybelle playing lead on a cheap Stella guitar.

The lyrics to “Single Girl, Married Girl” not only describe the deterioration of Sara and A.P.’s marriage, which ended in divorce in 1936, but they are also a stark comparison of the fates of married women and single girls in the 1920s. At that time, married women dedicated their whole life to taking care of the family. Single girls, often called “Flappers,” smoked, drank, wore their skirts short and their hair even shorter. Married women would have children, do laundry, make meals and feed the children, clean the house, and, in Sara’s particular case, chop firewood and plow fields. A. P. was gone from his home in the aptly named Poor Valley for extended periods, trying to sell cuttings from fruit trees and traveling extensively in many isolated communities throughout Central Appalachia with his friend Lesley Riddle, collecting songs from various singers and musicians that would eventually make their way into the repertoire of the Carter Family.

Even after gaining voting rights in 1920 (only white men could vote in the U.S. prior to 1920), women were not on equal footing with men in virtually all areas of life. Married women were expected to devote themselves to running the household, raising children and to acquiesce to their husbands’ judgment. At the beginning of the decade, most Appalachian women lived in rural areas without electricity. They had to keep food fresh without a refrigerator, iron with an iron that had to be reheated constantly, cook on a woodstove, go to an outside well for water, and always visit an outhouse instead of a bathroom. Rural electrification did not reach many rural Appalachian homes until the 1940s. Most Americans believed that women should not work outside the home if their husbands held jobs. If women did work, employers had the right to fire women after they married or had children, a practice that still plagues non-unionized women to this day. Single, divorced or widowed women also faced many challenges. Male co-signers, for example, were required for unmarried women to make any credit application.

Although divorce was more attainable in the 1920s than it had been in previous decades, it still carried a heavy stigma. There were few legal resources or options for women who were stuck in abusive relationships. One of my childhood friend’s entire family suffered greatly at the hands of an abusive father. His mother pled the Catholic church to grant her a divorce but she was ignored. Divorce was only allowed in situations where there was adultery, although exceptions were made in cases of bigamy or impotence. In cases of divorce, women had to prove that they were of sound mind if they wished to gain custody of their children. Divorced women were universally viewed as failures, too weak and unfit to be mothers.

Sara Carter married Coy Bayes, A. P.’s first cousin, and moved to California in 1943. The original Carter group disbanded in the late 1940s. Maybelle began performing with her daughters Helen, June and Amita as The Carter Sisters and Mother Maybelle (the act was renamed The Carter Family during the 1960s).

In 1949, guitarist Chet Atkins (1924-2001) left his Knoxville, Tennessee job to join up with the Carters. Their work soon attracted attention from the Grand Ole Opry, although Atkins was originally banned from all of their shows. Opry performers thought, and rightly so, that Alkins was too good a guitarist and would make everyone else look and sound foolish. They eventually relented and Atkins became a member of the Opry in the 1950s. Atkins began working on recording sessions and he is widely credited with creating the “Nashville Sound” which, for all its popularity, sank country music to the level of pop songs from the 1960s onward.

Speaking of the Piedmont singer-songwriter Dorsey Dixon (1897-1968), historian Dr. Patrick Huber said that he “possessed a rare gift for expressing complicated … social messages in an ordinary plainspoken language that is all the more poignant for its simplicity.” The same could be said of Sara Carter. In the context of early twentieth century American culture, “Single Girl, Married Girl” is not only one of the bravest songs ever recorded and a shining tribute to Sara Carter’s great ingenuity, it is also one of the most profound vehicles for social change to come out of American roots music.

“Single Girl, Married Girl” bears some similarities to Roba Stanley’s “Single Life”, recorded in 1925 when she was just 14 years old. Both songs, rooted in Appalachian folk culture, harshly indict marriage and motherhood for its suppression of women’s personal and social mobility. The appeal of roots music to a wider audience beyond those with immediate Appalachian connections is also evident in the immediate commercial success of “Single Girl, Married Girl” After their initial Carter Family recordings were released, Sara was surprised to see that “Single Girl, Married Girl” was the best-selling song when her first royalty payment arrived.

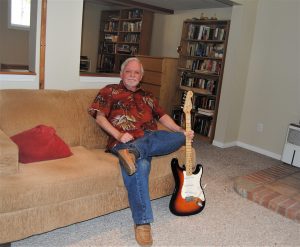

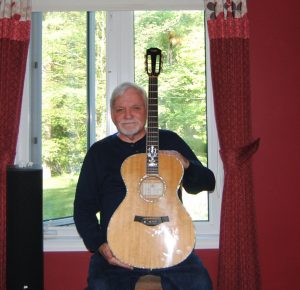

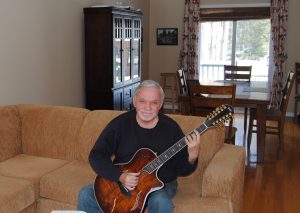

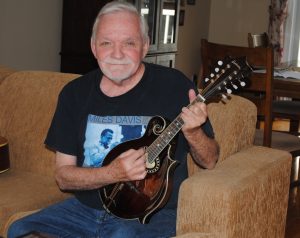

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, mandolin, banjo

Single Girl, Married Girl