It’s difficult to accept that a great bluesman like Joe Callicott lived his entire life in almost total obscurity. His date of birth is unknown, as was his age when he died in 1969. He was born and lived his whole life in the small town of Nesbit, Mississippi. Most likely illiterate, he gave no known interviews in his lifetime, wrote no letters or postcards. He married a woman and stayed with her for 52 years, until his death. He worked at the same workplace for 38 years.

Joe Callicott met up with Garfield Akers (circa 1902-1959), of whom even less is known, in the 1920’s and they became lifelong friends and partners, taking turns to play lead and second guitar as they sang at house parties, fish fries and various social events. In 1929, Callicott first appeared on four 78 rpm discs, playing second guitar to Akers. The pair were taken to Memphis by Jim Jackson (1876-1933), already a recording star and a Hernando resident and neighbour of Callicott. In 1930, Callicott also recorded two tracks with Jim Jackson.

Garfield Akers also toured with Frank Stokes on the Doc Watts Medicine Show and was active on the south Memphis circuit throughout the 1930s. No photographs of Akers are known to exist. He lived in Hernando, Mississippi, the community which also gave us several great bluesmen like Jim Jackson, George “Mojo” Buford, Frank Stokes and Robert Wilkins. For more about Frank Stokes and his music, click here. For more about Robert Wilkins and his music, click here.

Joe Calicott worked for PEMCO Aviation, a firm that specialized in passenger and freight services, for 38 years. He was an uneducated man and his work was likely handling freight, possibly in a custodial or janitorial capacity. His wages were certainly slight as Joe and his wife Sue Parrish Callicott (no data available) lived in abject poverty in a shack that a dog would think twice before entering. They had one son, Jeff.

Callicott almost completely gave up the guitar in 1959, the year Garfield Akers died, but picked it up again in the mid-1960s for his own personal enjoyment. In 1967, blues documentarian George Mitchell sought out Callicott and recorded eleven tracks with the then slowed down but still magnificent musician. These tracks would later surface in the 2003 album “Ain’t A Gonna Lie To You” Just before he died, in 1969, Callicott mentored Kenny Brown (b. 1953), a then 12-year-old white boy who skipped school to learn guitar from this unassuming master who lived just down the street. Kenny Brown went on to have a successful recording career, both as a guitarist and an artist.

Joe Callicott is buried in the Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery in Nesbit, Mississippi. On April 29, 1995, a memorial headstone was placed on his grave by the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund, an organization that memorializes the contributions of numerous musicians from the Mississippi Delta interred in rural cemeteries without grave markers. This final tribute to Joe Callicott was supported by Kenny Brown and financed by Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records and John Fogerty, of the Creedence Clearwater Revival rock band. Callicott’s original marker, an ordinary paving stone which simply read “JOE”, was subsequently donated by his family to the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi. At the ceremony the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund presented Callicott’s wife Sue with a check from Arhoolie Records for the royalties earned from a CD reissue of Callicott’s recorded works.

I have chosen to play Callicott’s “France Chance”, a raunchy blues that’s odd in many ways. The title comes from a rhyming scheme used in the lyrics. The structure is also odd since Callicott starts singing on the IV chord, while the singing for almost every blues song ever written starts on the I chord. Some of the lyrics can be cryptic. “Fair brown” is a term of endearment, i.e. fair brown-skinned woman. “Brand new stream” refers to an Airstream trailer, a high-end stainless steel marvel that looks like a bullet! The best blues lyrics are those that are equally plain and profound, perfectly evoked by Callicott’s brilliant :

I kmow my doggie when I hear him bark

I know my baby when I feel in the dark

It doesn’t get any better than that.

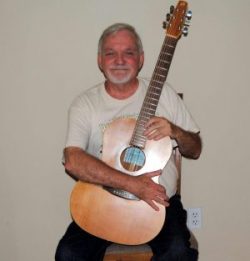

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, persussion