John Smith Hurt’s life (1893-1966) was like many others in rural Mississippi at the turn of the last century. He lived in Avalon, a flyspeck town on the Delta’s edge too tiny to show up on modern maps. He became a farmhand and sharecropper, like many others. If he set himself apart in any way it was by learning the guitar at the age of nine. Andres Segovia once said, speaking of the great classical guitarist John Williams : “God has laid a finger on his brow.” I believe that God then moved on to Avalon, Mississippi.

Growing up, John Hurt played for dances and parties, singing to his magnificent fingerpicking style, which sprang from a common source that produced both blues and country music. He was a link to a long ago past that still echoed in his playing : not blues, not country and yet both. His song “If You Don’t Want Me Baby” which I play here is a classic example of that genre. It’s lyrics are also so endearing, full of intimacy and longing. A simple sentence like “I tried so hard to do my father’s will” clearly states, without actually saying so, that the dutiful son did not succeed.

His music made Hurt popular with white and black Mississippians alike. In 1923, he met a white fiddler named Willie (William Thomas) Narmour (1889-1961) and they became a popular local attraction. In 1928, when Narmour won a fiddling contest and a chance to record for Okeh Records, he recommended John Hurt to his producers. After an audition, Hurt recorded two sessions, in New York City and in Memphis, which yielded 20 sides, only a few of which were ever released. The songs were issued under the name Mississippi John Hurt. Hurt never cared for the Mississippi label, which white producers believed would bestow authenticity on the performer, in much the same way as the designation “Blind” was believed to add respect and admiration to the artist. Sales of John Hurt’s records were poor during the Great Depression and Okeh Records went out of business in 1935, although it was revived a number of times in later years. John Hurt went back to the obscurity of his ordinary life in Avalon, Mississippi.

In 1952, a few of John Hurt’s early recordings were included in Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, which generated considerable interest among many folk enthusiasts in New York City. Ten years later, a full blown folk revival took over and many artists of the past resurfaced and enjoyed tremendous popularity during their later years.

Armed with the sole clue that Hurt had left about his life : a reference to “Avalon, my home town,” on a song called “Avalon Blues,” two white musicologists went to Mississippi in search of its author. They fully expected to find that he had died. With much difficulty, they located the village of Avalon and John Hurt’s cabin. Then 69, Hurt was astonished that anyone was looking for him. He didn’t trust white people in suits, always bad news back then, and had no inclination to leave his home town. Eventually, the musicologists encouraged him to move to Washington, D.C. and perform for a broader audience. His performance at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival caused his star to rise with the folk revival purists of that time. A creased and tiny man with wide and joyful eyes, Hurt was ushered onto the national stage to universal acclaim. However, by then he was a senior citizen with just three more years to live. He performed extensively at colleges, concert halls, and coffeehouses and appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. He also recorded three albums for Vanguard Records and much of his repertoire was also recorded for the Library of Congress. If the man from Avalon had any idea how important he was, he never let on. John Smith Hurt returned to his home in Avalon in the autumn of 1966 and died of cardiac arrest on November 2nd of that year.

Many guitarists who came of age in the 1960s and many others that followed were touched by the magic of John Hurt’s music and his warm personality. I was one of them but learning Mississippi John’s fingerpicking style also gave me a great deal of self worth that was otherwise lacking in my life. I owe him so much.

In 2003, John Hurt’s grand-daughter, Mary Frances Hurt Wright, having not visited Mississippi in quite some time, was suddenly taken with the need to revisit her grandfather’s home. As she stood there, contemplating the forces that had brought her back home, the man who currently owned the land that her grandfather’s house sat on remarked that “God had told him” that Mary would be there that day. He gave Mary the house. With $5,000 donated to her by a local Carrollton banker who remembered “Daddy John” playing guitar for his mother, Mary had the house moved to a two acre plot of land just up the road, restoring the house as a museum and a beacon to musicians and fans alike. Many of these fans travel to Avalon every year for the Mississippi John Hurt Music Festival.

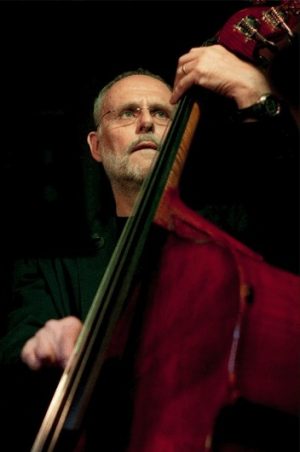

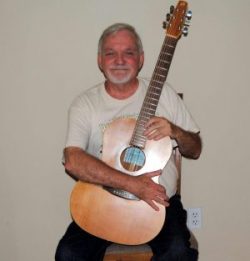

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, percussion (foot)