Such racial equality was a rare thing in the United States at that time. When I was a boy, the United States was a place of segregation in everything – human rights, public institutions, popular music, the record industry. In Canada, it was never an issue. I suspect that my parents were way too busy keeping a household of 9 people clothed and fed to bother with such things. My brother didn’t care and I never even once heard about the existence of different races as I grew up. I loved the music of Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis equally. I saw a picture of singer LaVern Baker at the age of 8 and she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. It never occurred to me that she was black.

In the early part of the 20th century, phonographs and phonograph records were most commonly distributed to white clients through furniture stores while blacks who could afford them bought phonograph records from Pullman porters working on the railroads that criss-crossed America. By the mid-1920s, all the major record companies in the U.S. were selling records made exclusively by and for African Americans, “race” records, as they were called.

Things remained the same until 1950, when a former disc jockey named Sam Phillips founded the Memphis Recording Service. Raised along side black people, working with them in the fields, Phillips recorded black amateur musicians and helped launch the careers of artists like B.B. King, Junior Parker, James Cotton, Rufus Thomas, Little Milton, Bobby Blue Bland and Howlin’ Wolf. The Memphis Recording Service also served as the studio for Phillips’s own label, Sun Record Company launched in 1952.

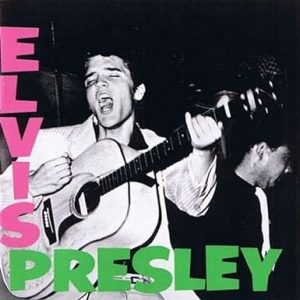

When he first heard Howlin’ Wolf, Phillips famously said “This is where the soul of man never dies.” What Phillips was searching for was a white man who could sing like a black man. As history would have it, that man was Elvis Presley (1935-1977). On July 18, 1953, Presley dropped into Sun studio to record a song for his mother’s birthday. Presley was what Sam Phillips had been searching for all along. Presley’s association with Phillips was a perfect storm. Phillips gave him the leeway and encouragement to go all out. They found the best songs for Presley’s exuberant style, some of them already recorded by then unknown black R&B artists like Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup (1905-1974) (That’s Alright Mama) and Junior Parker (1932-1971) (Mystery Train). Black songwriter Otis Blackwell (1931-2002) was also a major contributor with his compositions “Don’t Be Cruel” and “All Shook Up.”

To accompany Presley, Phillips used one of the best bands of the rock ‘n roll era, The Blue Moon Boys, with Bill Black (1926-1965) on upright bass, D.J. Fontana (1931-2018) on drums and Scotty Moore (1931-2016), one of the best guitarists in the history of rock ‘n roll. Elvis’ love of black R&B was apparent from the start – his first album in 1956 featured “Money Honey,” a song by Clyde McPhatter and The Drifters, and Ray Charles’ “I Got a Woman.” His electrifying live shows showcased his wild gyrations that no one had ever seen before. In short order, Elvis was featured on television shows hosted by the Dorsey Brothers, Milton Berle, Steve Allen and Ed Sullivan. In particular, 60 million people, or 82.6 percent of the viewing population, tuned in to watch the Steve Allen show.. Certainly, black artists like Chuck Berry had magnificent moves but they were slick while Elvis was raw. His gyrations certainly created a storm of controversy. The Catholic diocese in Wisconsin notified the FBI that Elvis was a threat to national security by arousing the sexual passions of teenaged youth. Many renowned music critics toed the line and one wrote that “popular music has reached its lowest depths in the ‘grunt and groin’ antics of one Elvis Presley – an exhibition that was suggestive and vulgar, tinged with the kind of animalism that should be confined to dives and bordellos.” Ed Sullivan, whose TV show was the nation’s most popular, declared Presley “unfit for family viewing.” To Presley’s displeasure, he soon found himself being referred to as “Elvis the Pelvis”, which he called “childish.” The Steve Allen show, in particular, introduced a “new Elvis” in a white bowtie and black tails. Presley sang “Hound Dog” for less than a minute to a basset hound wearing a top hat and bowtie. Presley would refer back to the Allen show as the most ridiculous performance of his career.Accompanying Presley’s rise to fame, a cultural shift was taking place that he both helped inspire and came to symbolize. The historian Martin Jezer wrote : “As Presley set the artistic pace, other artists followed. Presley, more than anyone else, gave the young a belief in themselves as a distinct and somehow unified generation—the first in America ever to feel the power of an integrated youth culture.”

After being drafted into the U.S. Army in late 1957, Presley reported to Fort Chaffee in Arkansas on March 24, 1958. They cut off his hair like they did for all recruits. He dressed like everyone else and was trained to obey. He went in the greatest Rock n’ Roll artist of his generation and came out looking like everybody else. Elvis Presley may have died in 1977 but to me and others, he died in 1958 at the hands of conformity. He returned to his career in 1960 but was never close to the artist he was in the 1950s.

Gillian Welch released “Elvis Presley Blues” in 2001 as part of her “Time (The Revelator)” CD. Her decision to insert into her song some of the lyrics from Presley’s 1956 hit “All Shook Up” is a stroke of genius.

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, mandolin, sampled percussion

To hear the song, click on the title below.

Copyright Disclaimer under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976 : allowance is made for « fair use » for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education and research.