I was lucky to be born into my family, at that time and in this part of the world. Unbelievably lucky. My brother Bob and a lot of our friends growing up feel exactly the same way. We all had perfect childhoods. If there was a downside for me, it’s that I was sheltered and completely ill-equipped emotionally for the brutal realities of the world outside my Prescott and Russell paradise.

Those brutal realities started piling up with the death of my brother Gabriel, everyone’s favourite, in 1959. Then I heard of the Cold War, the Berlin Wall in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. The world was on high alert – even my sleepy little village of Rockland started testing the big screeching alarm that was on top of the post office at that time. I had barely started high school when Kennedy was assassinated. And then, our neighbours to the south went completely crazy. The white ruling class declared all-out war on the black population.

In fact, this war had been going on for centuries but it was the increase in media coverage, especially television, that brought the horrors of the fire bombings of churches and the lynching of black men and women into our northern living rooms. I understood none of this because I didn’t grow up with prejudice and racism. My mother and father were way too busy keeping a household of nine people afloat to even think of such nonsense. When I was five, my brother Gabriel introduced me to his world of music, populated by black and white artists alike. My brother didn’t care – he loved them all. He was as crazy about Chuck Berry as he was about Jerry Lee Lewis. For every Elvis Presley record he had, there was an Ivory Joe Hunter record in his collection. For every record by the Everly Brothers or Buddy Holly, there were records by Little Richard, The Coasters or Fats Domino. I loved my brother and I grew up loving everything he loved. Consequently, my heroes have always been black and white. They still are.

By 1964, all the talk was about the Freedom Summer project, a voter registration drive aimed at increasing the number of registered black voters in Mississippi. Mississippi was chosen as the site of the project due to its historically low levels of African American voter registration; in 1962 less than 7 % of the state’s eligible black voters were registered to vote. Over 700 mostly white volunteers joined African Americans to fight against voter intimidation and discrimination at the polls. The movement was organized by civil rights coalitions like the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Freedom Summer volunteers were met with violent resistance from the Ku Klux Klan and members of state and local law enforcement. News coverage of beatings, false arrests and even murder drew international attention to the civil rights movement. The South remained segregated, especially when it came to the polls, where African Americans faced violence and intimidation when they attempted to exercise their constitutional right to vote. Poll taxes and literacy tests designed to silence black voters were common. Without access to the polls, political change in favor of civil rights was slow to non-existent.

Among the first wave of volunteers to arrive in June 1964 were two white students from New York, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, a local black man. The three disappeared after visiting Philadelphia, Mississippi, where they were investigating the burning of a church. It later came to be known that they had been arrested by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, a Klan member, ostensibly for speeding. They were held in jail until after nightfall, while Price organized a lynch mob of his fellow Klansmen. When the three were released, they drove into an ambush where Goodman and Schwerner were shot at point-blank range. Chaney was chased, beaten mercilessly, and shot three times. Six weeks later, the bodies of the missing volunteers were recovered, buried in an earthen dam. On December 4, the FBI arrested 19 suspects, all of them freed on a technicality. So started a three-year battle to bring them to justice. In October 1967, the men, including the Klan’s Imperial Wizard Samuel Bowers, who had allegedly ordered the murders, went on trial and seven were ultimately convicted of federal crimes related to the murders. All were sentenced from 3 to10 years, but none served more than six years. This marked the first time since the abolition of slavery after the Civil War, nearly 100 years, that white men had been convicted of civil rights violations against blacks in Mississippi.

Many of Mississippi’s white residents deeply resented the Freedom Summer activists and any attempt to change the status quo of segregation. Locals routinely harassed volunteers. Their presence in local black communities led to drive-by shootings and the bombing of the homes that hosted the activists. 37 churches were burned or bombed. State and local governments used arrests, arson, beatings, evictions, firing, murder, spying, and other forms of intimidation and harassment to oppose the project and prevent blacks from registering to vote or achieve social equality.

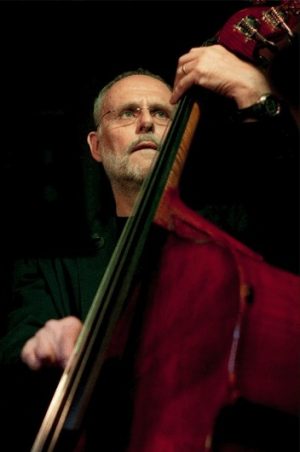

Witnessing all this from afar, I became a very unhappy 14-year old. People in my town kept to themselves and there was no one to talk to. Like many dejected young people of this era, I turned for inspiration and hope to the brilliant singer-songwriter who had recently taken North America by storm, Bob Dylan. Dylan was smart enough to know that the barriers built by hatred and bigotry would last all of our lifetimes and beyond. He sang that the answer was blowing in the wind. He saw that the civil rights movement and the folk music revival were closely allied and he wrote a song that he believed would be an anthem for change, called “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The song lyrics contained biblical references and were structured like some 18th and 19th century English, Irish and Scottish ballads like “A-Hunting We Will Go” or “Come All Ye Tender Hearted Maidens.” Less than a month after Dylan recorded the song, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. The song gave its name to Dylan’s next album, released in 1964 amid the fury of the very changes it predicted. Dylan sings the song accompanying himself on an acoustic guitar. My arrangement for “The Times They Are A-Changin’” is much more involved and depends greatly on the talents of my friends Alrick Huebener on upright bass and Roch Tassé on drums.

Looking back to 1964 now, it is very interesting to note that the southern States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, the hot spots of segregation and the prevention of housing, education and other services for people of colour, were all under the control of Democrats, today’s darlings. That year, on the floor of the U. S. Senate, Democrats held the longest filibuster in U. S. history, 75 days, all of them trying to prevent the passing of the Civil Rights Act. The Democratic governors and officials of state and local governments were some of the most evil men of the 20th century. And yet, Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, the man who fought to end slavery at the cost of his own life, was a Republican, today’s monsters. The truth is that evil men don’t care about political affiliations. Democrat, Republican, Conservative or Liberal are meaningless labels to them. Evil men depend on cloaks that hide their nature from you and me. Evil men will lay wreaths on the mass graves of indigenous children or on a memorial for the victims of the holocaust. They will read from prepared statements and repeat that their thoughts and prayers are with the families of the victims, always using those exact words, even though their thoughts are most definitely elsewhere and, of course, they never pray.We must all remember the words of Edmund Burke (1729-1797), an Irish politician who said “Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it.”

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, electric 12-string guitar, MIDI guitar (piano, organ)

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Roch Tassé – drums

Photo of Alrick by Kate Morgan