In 1964, Bob Dylan released “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”, which he sang while playing only an acoustic guitar. The lyrics read like a newspaper account of an incident that occurred at the Emerson Hotel, in Maryland, on February 9, 1963, where a 51-year-old black servant named Hattie Carroll was struck with the cane of a drunken William Zantzinger, a 24-year-old rich white patron of the hotel. Carroll died eight hours after the assault. Zantsinger was subsequently found guilty of assault and sentenced to six months in the county jail, a verdict that incensed many.

In 1965, Bob Dylan released “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, which he sang while playing an electric guitar, backed by Mike Bloomfield (electric guitar), Al Kooper (electric piano) and session musicians Paul Griffin (piano), Harvey Brooks (electric bass) and Bobby Gregg (drums). The lyrics describe a hallucinogenic vision of Juarez, Mexico, where the narrator encounters poverty, sickness, despair, prostitution, indifferent authorities, alcohol and drugs before finally returning to New York City. The lyrics make reference to works by celebrated authors like Malcolm Lowry, Edgar Allan Poe, Jack Kerouac and Arthur Rimbaud.

So what happened? How did Dylan change so completely in one short year?

Of course, some superficial manifestations of change like hairdos and clothes can be discounted. However, the change from acoustic to electric instruments was extraordinary and provided Dylan with many more colours to his palette. Electric instruments were a very important means of expressing the nuances of his new and obviously expanding world. He no longer sang about the politics that were corrupting and tearing American society apart. Afterward, Dylan sang of the whole world, with all its magic and all its aberrations.

From my point of view, throughout his early “protest” period, Dylan sang of things that happened in a foreign country. However righteous that I found his cause (and I did), I was aware that he had nothing to do with Canada. With a few and far between exceptions like Thomas D’Arcy McGee (1868), George Brown (1880) and Pierre Laporte (1970), we don’t assassinate politicians in Canada. Our restaurants serve all people, our motels welcome everyone and black people can even drink at public water fountains in Canada. It has always been so, as far as I know. We are not Americans and, starting in 1965, Dylan’s compositions left America to explore roads previously left untraveled.

Starting in 1965, Dylan sang words that defy the logic of the material world. He gave us unforgettable words like:

Yonder stands your orphan with his gun

Crying like a fire in the sun

or incredibly romantic phrases like:

The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face

Gone are the common words expressing bigotry and hatred. Here was a poet trying to describe the ineffable. The lyrics to “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” have caused much confusion to many people, beginning with the title itself. Tom Thumb is never mentioned in the lyrics and many believe the reference comes from Arthur Rimbaud’s Ma bohème (My Bohemian Life), where he refers to himself as a stargazing Tom Thumb. I believe the logic of the title can be found in the original book of The History of Tom Thumb. Tom’s story was originally intended for adults, but it was amended over the years and relegated to the nursery by the middle-19th century. Published in 1621, it was the first fairy tale printed in English. It relates a story from the days of King Arthur, where old Thomas of the Mountain wants nothing more than a son, even if he’s no bigger than his thumb. He sends his wife to consult with Merlin the magician and in three months time, she gives birth to the diminutive Tom Thumb. Several outlandish adventures befall our tiny hero – he proceeds to fall into a batter and gets cooked into a Christmas pudding, which he eats his way out of. Tom gets swallowed (and excreted) by a cow, carried away by a raven, and swallowed once again by a giant and a fish. I rather believe that Dylan makes an analogy between these fantastic hardships of Tom Thumb and the demoralizing situations related in the song’s lyrics.

Towards the end of my arrangement, I give a wink to The Beatles by incorporating their composition, « I’ve Just Seen A Face, » into our playing. I must also recognize the inspired contributions of Alrick and Roch, two of the finest musicians of our region.

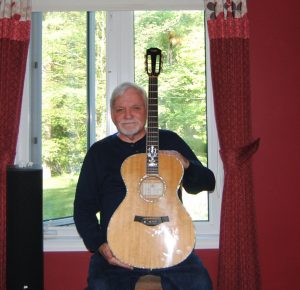

Richard Séguin – voice, 6 and 12 string acoustic guitars

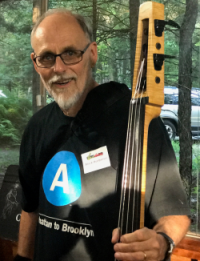

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Roch Tassé – drums