Growing up in a rural environment as part of a large stable family, playing outdoors with lots of friends, I was incredibly happy as a child. I managed to endure, perhaps not all that well, the loss of my grandparents and of my brother Gabriel. However, starting with the Cuban Missile crisis in late 1962, what I failed to endure was the existence of foreign political leaders who threatened the survival of all life on this planet. I started hating people I didn’t know who interfered with my perfect life, as if they were entitled to decide other people’s fate. This wasn’t the life I wanted and for the first time, I was unhappy. Then things got worse.

I had just started high school when Oswald shot Kennedy. Then Ruby shot Oswald and later died of a pulmonary embolism at Parkland Hospital in Dallas, the same place where Kennedy and Oswald died. Then James Earl Ray shot Martin Luther King Jr. and Sirhan Sirhan shot Bobby Kennedy, both in 1968. I was (and have been ever since) conscious that I was living next to a nation of barbarians. Any nation whose citizens are legally entitled to bear arms is, by definition, a nation of barbarians. To this day, I thank Providence that they didn’t shoot their harshest critic, a man who lived long enough to actually make a difference – Bob Dylan.

I followed Bob Dylan because he spoke of everything I was anxious about. In 1962, “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an anthem for the Civil Rights Movement. In 1963, racist Byron De La Beckwith assassinated black Civil Rights activist Medgar Evars. Dylan responded by singing “Only a Pawn in Their Game” at the Freedom March on Washington in 1963, where doctor Martin Luther King Jr. pronounced his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Still in 1963, Dylan published the album “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, a dire warning about the escalating arms race. Violence and protest were everywhere in 1964 when he published the album “The Times They Are A-Changin’”, an obvious understatement.

Dylan never actively sought the fame and adulation that surrounded him every waking hour of every day. An entire generation of young, educated people expected him to be the saviour of their troubled existence but Dylan was always an outsider. While the entire music industry, everyone from The Byrds to Mitch Miller, from Harry Belafonte to Duke Ellington, tried to grab a piece of Dylan’s pie by recording hundreds of versions of his songs, Dylan was moving in a different direction, his music gradually acquiring a blues edge intensified by the addition of electric instruments. It started with his 1965 album entitled “Bringing It All Back Home,” where some magnificent acoustic songs were featured next to a few electric songs that revealed a different Dylan, an exceptional lyricist whose consciousness seemed to be exploding.

Dylan returned from an exhausting tour of England (see D.A. Pennebaker’s 1965 documentary “Don’t Look Back”) and went into the studio in June, 1965 to record “Like a Rolling Stone.” The song went through different tempos, multiple pages of lyrics, a trial ¾ time signature and a number of musicians, the two most famous being Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper. Bloomfield, the fiery guitarist from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band who Dylan said was the best guitarist he had ever heard, was an easy pick. At that time, Al Kooper was a 21-year-old guitarist invited by producer Tom Wilson to take part in the session. When Kooper heard Bloomfield play, he put his guitar back in its case and moved to the control booth! When Wilson moved a musician from organ to piano, Kooper bluffed Wilson into believing he had a perfect organ part for the song. Wilson scoffed at him but didn’t say no and when Dylan heard Kooper play, he told Wilson to turn up the volume on the organ. Wilson protested that Kooper didn’t know how to play the organ but Dylan got his way and the most famous organ part of the decade was born.

Because of concerns from the sales and marketing departments over the song’s unprecedented six-minute length and “raucous” rock sound, “Like a Rolling Stone” was initially rejected by Columbia Records. A discarded acetate of the song made its way to a New York disco and was quickly worn out completely at the demands of the crowd. On July 20, 1965, “Like a Rolling Stone” was released as a single with the acoustic gem, “Gates of Eden” as its B-side.

According to review aggregator Acclaimed Music, “Like a Rolling Stone” is the statistically most acclaimed song of all time. Rolling Stone magazine listed the song at No. 1 in their “500 Greatest Songs of All Time” list. At an auction in 2014, Dylan’s handwritten lyrics to the song fetched $2 million, a world record for a popular music manuscript. In an interview with CBC radio in Montreal, Dylan called the creation of the song a “breakthrough”, explaining that it changed his perception of where he was going in his career.I was 15 when I first heard “Like a Rolling Stone.” I was walking through the school cafeteria, a radio was playing in the back and when I heard that first snare shot, what Bruce Springsteen said “sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind”, followed by Al Kooper’s sublime organ, I stopped dead in my tracks. I didn’t move for 6 minutes.

Immediately after the release of “Like a Rolling Stone”, Dylan went on a tour that encompassed three continents. He was booed, threatened and assaulted everywhere he played. Why? The band played electric instruments. The dynamics between acoustic and electric performances are opposite. In an acoustic performance, the direction is toward the artist, the audience listens, pays attention and there is a personal bond with the artist. None of that exists in an electric performance. The direction is toward the audience, loud, agressive and imposing. In Dylan’s case, the personal bond with the audience was lost, which was perceived as a betrayal.

At the Newport Folk Festival Pete Seeger threatened to cut the wires to the amplifiers and Dylan was booed off the stage after three songs. He was coaxed back, acoustic guitar in hand, to prophetically sing “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” At Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in New York, fans booed and rushed the stage. This insane period is perfectly captured in Martin Scorsese’s excellent documentary about Dylan in the 1960’s called “No Direction Home”, the title taken from the lyrics to “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan is clearly shown as a progressively frustrated and hopeless artist in the face of an insensible public and even more senseless media. He talks of “having enough with the whole scene and quitting for a while.” As it turned out, this decision was made for him. After returning home from the tour and finishing yet another masterpiece recording with “Blonde On Blonde”, Dylan was involved on a serious motorcycle accident on July 29, 1966. The incident is clouded in mystery. No police report was ever filed. Dylan did not go to a hospital. He spent three months in the third-floor bedroom of a local doctor he knew.Dylan continued writing and recording but his music was never the same. Different but still great – “All Along the Watchtower” from Dylan’s 1967 album “John Wesley Harding” made Jimi Hendrix a household name. However, it took eight years for Dylan to tour again.

Once again, all my thanks go out to Roch and Alrick, two of the best musicians I have been lucky enough to know.

Richard Séguin – voice, 6 and 12 string acoustic guitars, electric guitars, MIDI guitar (organ)

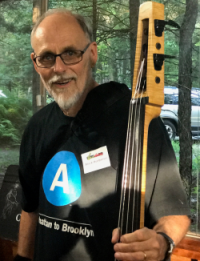

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Roch Tassé – drums