The folk and blues revival, one of the most important cultural phenomenons of the 20th century, started in the 1950s in the coffeehouses of Greenwich Village, a bohemian district of New York City. The first showcased artists were the so-called “beat” poets, who would occasionally complement their verse with the rattlings of a drum kit or the low rumblings of an upright bass. Local musicians followed, including now famous names like Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives, Josh White, Lead Belly, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, the Kingston Trio and the Reverend Gary Davis. In the 1960s, young, white musicologists also searched the southern rural areas, looking for the great bluesmen whose careers were mostly cut short by the Great Depression. Some had died but many were found and came to New York City to play in front of young, white, educated audiences in the coffee houses, colleges, universities and folk festivals throughout the eastern United States. For the first time in their lives, these artists were revered and praised like they never had been in the South, where segregation still ruled.

When Eddie James “Son” House (1902-1988) came to New York City in 1964, he brought with him a repertoire of songs that straddled the sacred and the profane. A Baptist minister in his early years, Son House devoted himself to religious music and openly rejected the blues as “the Devil’s music.” Things changed with the Great Depression and House’s friendship with bluesman Charlie Patton (1891-1934) led him to the bars and roadhouses of the South to earn a living.

I heard Son House and saw him on TV in the late 60s and was completely conquered by his immense talent. I was especially moved by his masterpiece, “Death Letter,” which I recorded in 2019 with Roch and Alrick. To hear the results, click here.

House was a door to the past and the pure fire of his religious songs left no one indifferent. Chief among these, for me, was “John the Revelator.” an apocalyptic text and the final book of the New Testament, secured by seven symbolic seals, the opening of which brings on the Apocalypse. The identity of the author of the Book of Revelation has been in much dispute throughout history but is often attributed to John of Patmos. The song was described by critic Thomas Ward as one of the most powerful songs in all of prewar music.

Blind Willie Johnson (1897-1945), himself an evangelist, recorded “John the Revelator” during his fifth and final session for Columbia Records in 1930. Son House recorded several powerful a cappella (without instrumental accompaniment) versions of “John the Revelator” in the 1960s. House’s lyrics, very different from those sung by Blind Willie Johnson, reference important theological events like the Fall of Man, the Passion of Christ and the Resurrection. I added the last verse about Moses, which comes from the Blind Willie Johnson version.

The Book of Revelation contributed vastly to our popular culture through the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, viewed as harbingers of the Last Judgment. They are said to bring with them war, infectious diseases, famine, economic collapse and death. Over the centuries, the Book of Revelation was interpreted by many sects and I would caution that they be taken with a grain of salt. One interpretation insisted that the First Horseman was the Antichrist, specifically Napoleon Bonaparte. We see the influence of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in all aspects of our culture, including movies, literature, music, comic books, television and video games.

Richard Séguin – voice and finger snaps

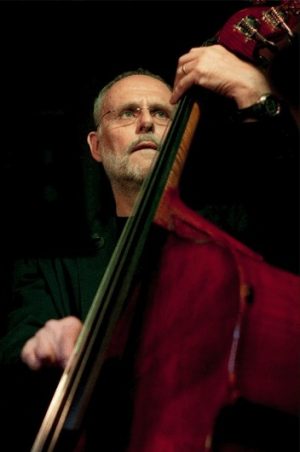

Alrick Huebener – upright bass

Photo of Alrick by Kate Morgan

Ajouter un mot

You must be logged in to post a comment.