Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album entitled “Nebraska” started as a cost-cutting measure to reduce the studio time that was required for his E Street Band to put together new songs. Initially, Springsteen recorded demos for the album at his home with a 4-track cassette recorder. Listening to the results, the consensus was that the songs were very personal and that the raw, haunting folk essence present on the home tapes could not be duplicated or equaled in the studio with the E Street Band’s brand of fiery, expansive rock & roll. Springsteen decided that these stories were best told by one man, one guitar. It was a bold decision to release the initial recordings as is.

“Nebraska”, the title song, refers to Charles Starkweather, who senselessly murdered eleven people in Nebraska and Wyoming between December 1957 and January 1958, when he was 19 years old. During his spree, Starkweather was accompanied by his 14-year-old girlfriend, Caril Ann Fugate. The song certainly sets the tone for the rest of the album : many of the songs are stark, violent and full of despair. Others, like “My Father’s House”, are deeply personal and drawn from Springsteen’s past, in particular his complicated relationship with his father.

In 2009, several artists performed at Washington, DC’s opulent Kennedy Center to honour Bruce Springsteen’s life and music. During the ceremonies, Jon Stewart famously said “I believe that Bob Dylan and James Brown had a baby. And they abandoned this child on the side of the road, between the exit interchanges of 8A and 9 on the New Jersey Turnpike. That child is Bruce Springsteen.” Ben Harper also performed an abbreviated version of “My Father’s House” which left the audience either speechless or in tears. I have borrowed a few parts of Harper’s brilliant rendition.

“My Father’s House” has a special meaning for me and our family. My sister Diane was born in late 1951 and my father already knew that his rented house next to Annie Powers, our town’s celebrated doctor, would no longer comfortably hold nine people. We were to be six kids and my grand-father Villeneuve was also part of the family. My father started building a house of his own design, with the help of friends, relations and neighbours, the way things were done in our francophone community at that time. We moved into our new house in 1952.My childhood, growing up in my father’s house, in our small community, was as perfect as any childhood can be. We were comfortable. My parents had their bedroom on the ground floor and everybody else slept upstairs. My two sisters had their own bedroom, as did my grand-father, and the four boys shared a large room that featured two double beds – the elder boys, Jean-Guy and Gabriel in one bed, my brother Bob and me in the other. I always felt safe.

My grandfather was a man from a different world, a contemporary of Wyatt Earp, Jesse James and Mark Twain. He was as strong as an ox and as imposing as a tree. He was kind and built us wooden toys in my father’s downstairs workshop. His wonderful, silent presence stays with me still and I wrote an instrumental piece in his honour, which you can hear by clicking here.

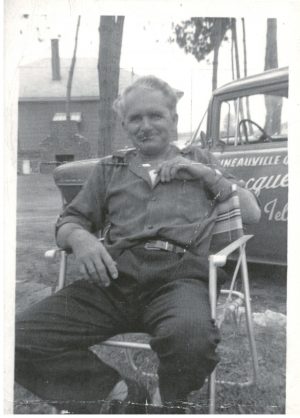

My father, Jean-René Séguin (1908-1975), was a Renaissance man. Born in Rockland, he started working at the age of twelve, trying to support his family. This was the fate on many boys at that time. My father would get up early, have breakfast and walk to the Ottawa River where he had a rowboat moored on the shore. He crossed the river, anchored his boat, and worked all day in the forest industry in Thurso, cutting down trees and doing whatever other work was required. At the end of the day, he crossed the river to the Ontario side and walked home for a late supper. He was paid a dollar a day.Even though he only had a grade 6 education, my father mysteriously understood mathematics. He regularly produced blueprints for many local builders and they always met all provincial standards, at a fraction of the cost that a professional architect would have charged. He was the only one in town who could build a staircase, a very complicated, formulaic operation involving the relationship between tilted angles, horizontal angles and height. His workshop featured a lathe and he made some astounding things, everything from elegant, curved table legs to two-toned wooden salad bowls. He stopped at nothing to care for his family, even trapping for furs. Our basement often had furs drying on wooden frames and he even had a whole bear skin in the basement which my brother Bob donned to scare the daylights out of me. He even dabbled in taxidermy for various clients. For relaxation, he built scale models of locomotives installed on a sheet of plywood, complete with water towers, tunnels, bridges and depots, all done to scale.

All the members of our family were fortunate to have a father like ours. I play “My Father’s House” in his memory.

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitars, mandolin