I grew up in a houseful of nine people spanning three generations. I was always surrounded by love, from my grand-father, my father and mother and from my brothers and sisters. My brother Bob was closest in age and he was, and still is, a great older brother. My older sister Marielle, 10 years my senior, was my baby-sitter and surrogate mother when my mother’s time was entirely devoted to looking after the daily needs of nine people.

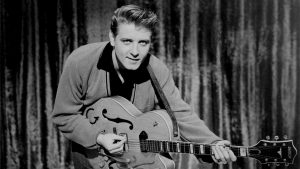

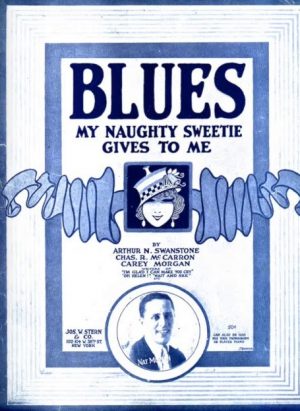

And then there was my brother Gabriel, 14 years my senior. You would have thought that a young man would have other things on his mind than the small world of a child but Gabriel was never what you would have expected. Sure, he had girlfriends, worked as a civil servant, water skied and played his piano with his small combo but he always found time to be attentive, which was his nature, and not just with me but with everyone. When he saw that I was captivated by the incomprehensible beauty of music at the age of five, he took me aside, showed me how to take care of his record collection and taught me how to work our gramophone. Gabriel allowed me to play his records any time I wanted, just like a grown-up. And he opened the door to my life-long love affair with music, the greatest gift I have ever received, after his love. My brother’s record collection was second to none. Every artist who shaped the first wave of rock n’ roll in the 50s was there – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ivory Joe Hunter, The Everley Brothers, Buddy Holly, The Coasters. When I was 8, a new artist came into the collection – Eddie Cochran. My brother bought three of his biggest successes, “Summertime Blues”, “C’mon Everybody” and “Somethin’ Else.” Cochran was a young, good-looking, strutting rock-and-roller who always played a magnificent Gretsch 6120 electric guitar with a Bigsby tailpiece. I’ve chosen to feature Cochran’s “C’mon Everybody”, played very close to the original 1958 recording.Like Chuck Berry, Cochran sang songs of teenage frustration and rebellion which are still admired to this day. Cochran’s rise to fame was nothing short of meteoric. He learned music at an early age and released his first recordings at the age of 17. The same year, he was featured in the Hollywood film “The Girl Can’t Help It”, performing another one of his hit songs, “Twenty Flight Rock.”

In early 1959, two of Cochran’s friends, Buddy Holly and Richie Valens, along with the Big Bopper (J.P. Richardson), were killed in a plane crash while on tour. Cochran was badly shaken by their deaths, and he developed a morbid premonition that he would also die young. Shortly after their deaths, he recorded the song “Three Stars” as a tribute to them. He was anxious to give up life on the road and spend his time in the studio making music, thereby reducing the chance of suffering a similar fatal accident while touring. Financial responsibilities, however, required that he continue to perform live, and that led to a tour of the United Kingdom in 1960. Cochran was on tour in England when he and fellow performing artist Gene Vincent were traveling in a taxi towards London. In addition to Cochran and Vincent, the other passengers in the vehicle were Sharon Sheeley, a 20-year-old songwriter who was also Cochran’s fiancée at the time, Patrick Tompkins (the tour manager, 29 years old), and George Martin (the 19-year-old taxi driver). Towards midight, Martin lost control of the vehicle, which crashed into a concrete lamppost. At the moment of impact, Cochran (who was seated in the center of the back seat) threw himself over Sheeley to shield her. The force of the collision caused the left rear passenger door to open and Cochran was ejected from the vehicle, sustaining a massive blunt force trauma to the skull. The road was dry and the weather was good, but the vehicle was later determined to be traveling at an excessive speed. The occupants of the vehicle were all taken to Chippenham Community Hospital and later transferred to St Martin’s Hospital in Bath. Cochran never regained consciousness and died at 4:10 p.m. the following day – Easter Sunday. He was 21 years old. Sheeley suffered injuries to her back and thigh, Vincent suffered a fractured collarbone and severe injuries to his legs, and Tompkins sustained facial injuries and a fracture of the base of the skull. Martin did not sustain significant injuries. In between the tragedies that befell Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran, my family sustained one of its own when my brother Gabriel accidentally drowned on the 28th of June 1959, at the age of 23. They called Buddy Holly’s death the day the music died but, for me, the music died with my brother. However, what my brother gave me has never died and, four years after his death, I picked up my first guitar.Photo of Eddie Cochran (public domain), Eddie Cochran – Singer Facebook page

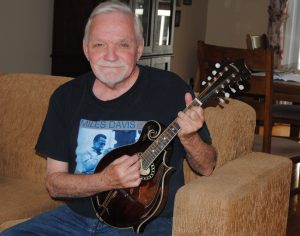

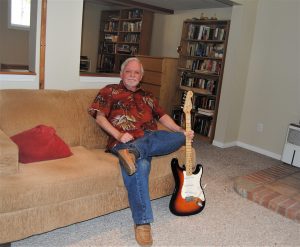

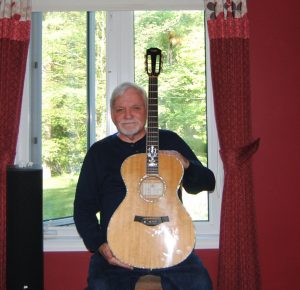

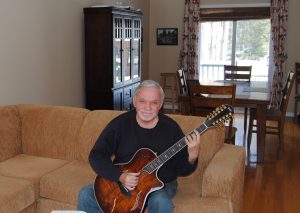

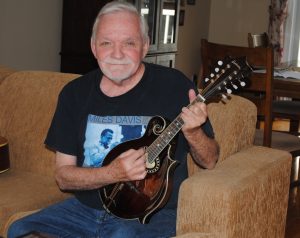

Richard Séguin – voice, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, mandolin, electric bass, percussion

Roch Tassé and Linda Challes – percussion

To hear the song, click on the title below